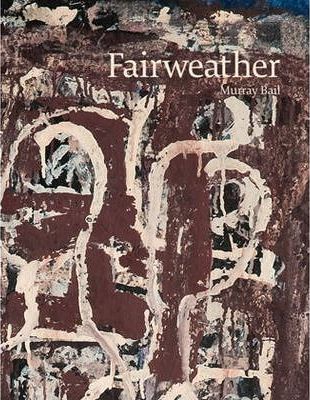

Front cover of Murray Bail’s seminal biography of the Scottish-born Australian artist Ian Fairweather

Ian Fairweather by Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz

Every retrospective exhibition is worthwhile for those who wish to study art, and the exhibition of the work of Ian Fairweather in the National Gallery [AGSA] gives the onlooker at least an idea of how the artist achieves the final phase of his development. Probably they would not consider this phase as important a contribution to art in Australia as his early period.

In the landscape and figure stud[ies] of his early work, he begins to animate objects successfully, but it is still only a discipline imposed upon his personal sensitivity. His baroque-like early paintings are the beginning of his departure to his extremely personal style. The robust lines which appear in the latest pictures are the result of those pencil lines clearly seen in his early paintings, which developed to his brush lines of the semi-abstract on such huge canvases. The early discipline of freely handled pencil lines lead to the vigorous brush curves which give proof that he broke completely away from the classical prettiness through the study of Chinese calligraphy.

In his last stage, different pictures arrive in solemn, organic forms. One can say that he redresses the European character of his work through the universal theme of people, into a critical simplicity transforming them into unknown surroundings of primitive-like eternity and sharply creates a transparency of background in which human bones and anatomical details from the static classical sense disappear. Those abstract lines liberate the paintings from his previous baroque schooling (No. 7) and introduce to us a contemporary mosaic on a high aesthetic level. Deliberate simplification of figures, disintegration of the two-dimensional forms by strokes and lines with light from the background make those figures move in magical rhythm – an organic harmony of dramatic clumsiness.

Every picture with those dark lines is free from static masses and yet suggest[s] realism through its artistic objective and emotional approach.

Ian Fairweather consciously discarded his previous pictures which only suggested the imitation and illusion of nature. He resigned from using perspective models and other literary means, but many of our painters today would be happy to have achieved as much as he had done at that stage. Years of experience and a long devoted life to art, allowed him to create a sufficiently organic style comparable to the language of forms in shorthand – a style in which elementary forms inherit a simplicity of compact lines and colours. By simplification I mean reduction of mass by linear structure, or that the open planes superimposed on the contours of the figures are not a point of departure only, but are sharply defined contours of existence in the universe. The veteran artist’s inner experience comes to the surface like magic gestures of the spring of life.

Some criticism can be levelled at the poor material which he uses – cartons, cardboard, which is already buckled, and second-hand masonite scraps which he has joined together.

Criticism can also be made of the framing which he had definitely done himself, and which now deserves to be changed to a better quality by collectors. In his early work he used oil on cardboard and gouache. Some oil is already cracking – probably he has used house paint. All other works of his second phase are mostly painted in tempera or self-made colour.

But Ian Fairweather’s work cannot be dimmed by things of such minor importance, which cannot camouflage the heights to which this hermit has already climbed during his long life.

Originally published in Kalori 3, no 4 (Dec. 1965), p. 14 (ed. Betty Jew)