Brian Claridge, letter to Kultura, Paris, dated 30 June c.1955

The Polish-Australian artist, Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz, has developed his own particular form of expression. Two things were responsible for this. The first was the desire to escape the direct influence of any previous master, and not to merely continue to exploit an idiom already established. The second was the belief that there must be a way by which an artist can keep working without having to wait for his inspiration to suddenly happen – that he should not have to rely on the good fortune of a heaven-sent inspiration, but should be able to discover inspiration for himself by working with this in view.

An account of the method of working that Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz evolved as a result of these impulses is included in the enclosed paper.

There are two important consequences of this method outlined. One is that a most significant expression has resulted which I believe is a definite and important contribution to art. The artist has achieved, in those of his paintings which are so far based entirely on the method, work that must take its place in world art as advancing beyond the so far accepted artistic expressions. The other point that emerges is the possibility that this method as applied to painting is a particular aspect of a more general inception that will have applications in other arts and other fields of thought. It is this possibility in which we are now interested. This is suggested at the end of the paper.

So far, tentative experiments have been made in music and poetry, and with sculptural and architectural forms, with encouraging results.

I cannot help feeling that it is significant that, with Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz expressing his ideas purely in the terms of a painter, he has been able to give to non-painters the suggestion of a new approach in their own work (architecture in one case, music and poetry). This must mean that, somehow, he has been able to communicate through particular terms a more general conception. Although this has not actually been expressed, it has, nevertheless, been intuitively grasped and worked upon. This strongly points to the possibility of there being a more general and fundamental expression of his idea that, once formulated, could prove useful in many other fields of activity.

It was to consider this point that the enclosed paper was prepared and recently presented to a selected group of possibly interested people. Not all of them were necessarily familiar with the development of modern art. It was hoped to discover the reactions of others who may be regarded as authoritative in their respective spheres.

Those chosen were (i) a physicist with an interest in but apparently no deep feeling for or knowledge of art; (ii) the Professor of Philosophy at the Adelaide University who showed no feeling for art; (iii) the resident conductor of our Symphony Orchestra who is a scholar of music and a composer as well as an art lover; (iv) a lecturer in philosophy who has, apparently, a knowledge and appreciation of art; (v) a local art collector, dilettante – a most widely read and informed person with very definite opinions.

The general view of these people seemed to be an acknowledgement that the artist’s method was worth considering, but that it was, perhaps, only one of several methods that could give similar results. Little was said about the possible extension of the method, although the musician could see a limited application almost at once, and had a better appreciation at the end of the discussion. The last mentioned in the group above has subsequently said that he has tried the method and found it useful in drawing in which he is interested.

But generally, the people were unable to enter into the spirit of the idea, not able to rise above being specialists. They lacked the imagination to see possible applications of the way of working. I feel that here in Adelaide – and possibly in Australia – it would be well-nigh impossible to find authoritative people with an appreciation of arts and minds flexible enough to escape the limits of their particular line of thought to discuss and develop the idea with.

Further, artists with whom we’ve discussed it have only vaguely claimed either that they are doing something similar when their work proves conclusively that they are not, or that there are plenty of others already doing it, but cannot give any example when asked for it.

My reason for writing to you is that I feel it would be interesting to discover if there are any people working in this way at all, and to exchange ideas with them. This is the sort of investigation that needs sympathetic and creative minds working together, as has been the case with significant art movements. As we have not yet found such people in Australia, we are looking for ways to find them abroad.

I would greatly appreciate it if you or any of your writers would consider the suggested extension of the artist’s method. If you feel that it is worthwhile, perhaps you might publish something of these details in Kultura. Through this, interested people may have a chance of working together.

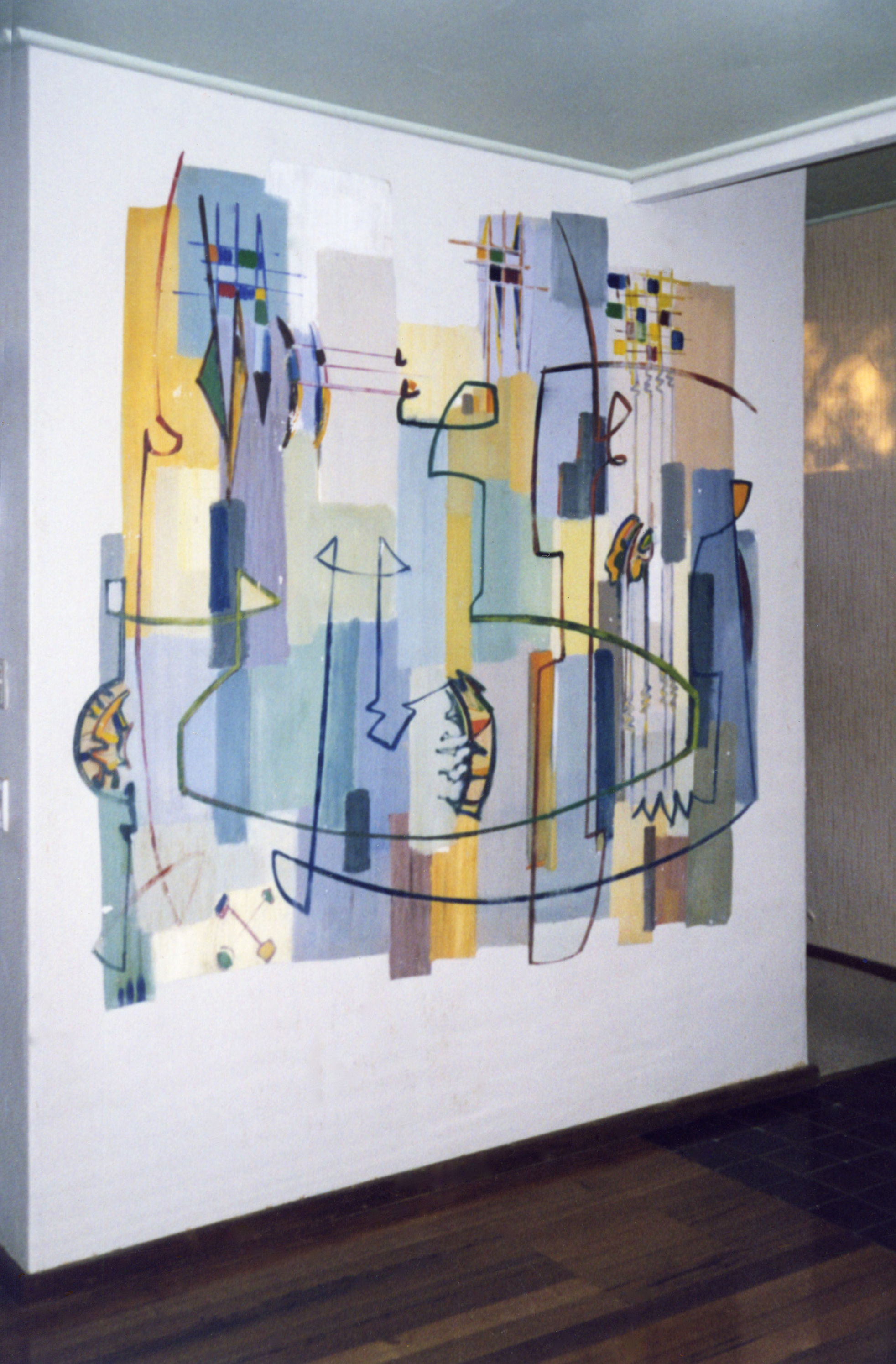

I am enclosing one or two reproductions of Dutkiewicz’s work which I hope will give you an idea of his work. One is a mural in my home that represents an earlier development of his method.

[Handwritten letter ends]

***

[On Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz’s “Theory of Light and Line”]

The role of the artist is to establish relationships between man and his world – to make new realms of feeling accessible – to give an emotional significance to aspects of our life that normally lack it.

This has been done by artistic methods which have been derived from the physical appearance of our world, or from the scientific knowledge that attempts to explain it, or has been done simply by intuition.

Further, the art of any era has only made real contributions toward establishing new relationships between man and his world when the methods have been consistent with the thought and knowledge of the time.

These methods, however, have always given rise to forms of expression in terms of man himself – man as existing in space and time interpreting other things and phenomena existing in space and time. Art has never appeared to seek further than this, although there have been philosophical suggestions that our experience of the world does not represent the true nature of things. This view has developed from Kant, who maintained that space and its characteristics and time are products of our consciousness. The placing of things in space and time exists only in us, and not in the things themselves.

No form of artistic expression has taken such ideas into account. Since the beginning of this century when these ideas, first suggested by Kant, were at last taken up by others, modern art, too, has developed forms of expression in terms of man himself – not in terms of man outside himself.

One of the last and most important statements in art considered to be in line with today’s thought and knowledge is that of the Cubists. This appears to be consistent with the new space-time conception described by Einstein and Minkowski [1] with the simultaneous representation of various aspects of the one object, regarded as an artistic parallel to the ideas of relativity. We can no longer think it possible to fully describe an object from a single point of reference – a moving point of reference is necessary to fully comprehend an object.

But the cubist approach – the simultaneous representation of several facets of the object or group of objects is really just as inadequate as the single aspect represented by classical perspective. The cubist statement, from two or three, or even a hundred points of reference, all still with a definite relationship to the object, falls as far short of the infinite number of random points of reference suggested by the notion of relativity as does the single aspect presented by classical perspective. The cubist attempt to achieve full description now appears naive and inadequate. It can be regarded only as a first approximation – nevertheless an important one – to an art form fully parallel to our new space-time conception.

In the developments of cubism which were purely abstract, with no reference to any specific object, the art possesses no qualities in any way related to this conception. The moment the object is abandoned, the cubist approach loses its true and original significance. We find the artists returning to colour and texture, as, without the object, they have nothing to say other than in colour and form harmonies.

Of the artists concerned with abstract art and not connected with the cubists, Kandinsky stands as most important, and something of a prophet. In his writing as well as in his painting, he tried to establish the principles of artistic harmony and counter-point, and was concerned with the psychic effect of forms on man. He abandoned objective painting in favour of abstract because he feared obscuring pure art by the emotions aroused by objects. He loved ‘only form that comes of necessity from the spirit, and had been created by the spirit’. He maintained that ‘the Philosophy of Art will in the future study with particular attention the spirit of things as well as their physical existence – an atmosphere will be created which will enable the human race to feel this spirit in the same unthinking way it now appreciates external appearance – and through this, the spirit of matter and finally the spirit of the abstract will become quite evident to humanity. From this new faculty will spring the joy of pure abstract art.’ [2]

Here is the suggestion that there will come an artistic expression which is derived from consideration of things outside of man and his space-time world – that art will be animated by the ‘spirit of things’ – not of particular things, but of all things – rather than by their outward appearance.

Kandinsky, though sensing the future course of art, did not himself go beyond the ‘musical’ aspect of art, his expression being based on the intuitive harmonies, rhythms and counterpoints of lines, colours and forms which comprise his Compositions.

Just at the time that Kandinsky was working and thinking in this direction, the challenge of Kant was again being taken up, and a first understanding of the problem he posed becomes evident. A new approach to the problem of space and time involving the conception of ‘the fourth dimension’ appears.

Kant asserted that everything known to us through the senses is known in terms of space and time, and, by the senses, we know nothing outside of space and time. Kant established the fact that extension in space and existence in time are not properties belonging to things, but are just the properties of our sensuous receptivity. In reality, apart from our sensuous knowledge of things, they exist independently of space and time. Perceiving things sensuously we impose upon them the conditions of space and time. Space and time, then, do not represent properties of the world, but are properties of our knowledge of the world which, in reality, has neither extension in space or existence in time. We require these aids for perceiving the world. A thing having no definite extension in space or existence in time has virtually no meaning for us. A thing not in space will not differ from any other thing in any particular, and may occupy the same place simultaneously with any other thing. And all phenomena not in time – not regarded in relation to past, present, and future would co-exist for us simultaneously. Our consciousness isolates things for us into categories of space and time, but the division exists only in us and in our knowledge of things, and not in the things themselves. Kant left the problem here, suggesting we could never know the real thing itself outside of space and time by nature of our psychic make-up. Schopenhauer, however, suggested we could, through intuition. Later suggestions are that it is possible to develop a higher psychic constitution which will enable us to really know things as they exist independently of space and time. This is the thought based on the conception of the ‘fourth dimension’.

This assertion of the existence of things outside of man’s perception of them – in no relation to the man-imposed divisions of space and time – is suggestive of Kandinsky’s idea of the spiritual aspect of things which he predicted would be the concern of the art of the future, and which goes beyond the mere physical appearance of things.

This leads to an art form in which the expression is not in terms of man himself and his sensuous knowledge of the world, but rather an expression which acknowledges the existence of things in themselves, outside of man. Such expression will result in the creation of new forms which will be derived from the discoveries of a consciousness roaming freely outside the limitations of space and time.

The new forms will exist in their own right, without reference to man’s sensuous knowledge of the world, without any particular reference to how man perceives the objective world, or how science suggests he might see it. The forms will be universally valid as regards the observer’s position in space and time. This, incidentally, will represent the true parallel between an artistic expression and the philosophical and scientific knowledge of our time.

The artistic forms will appear in a way similar to that which may be considered to be the way things, outside of man’s knowledge of them, have come to exist.

The art of Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz is an expression of this kind. It is an art form that takes man outside of himself. It is a first realisation of Kandinsky’s prophecy. Forms result from an understanding of the independent existence of things.

The method W.D. has evolved was arrived at purely intuitively from the desire to produce paintings in a manner entirely new, and which were in no way derived from the methods so far employed.

Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz starts with a series of arbitrarily chosen points in space, inside or outside the limits of the canvas. These are in no particular relationship to each other or to the artist. From any point to any other, pairs of lines are drawn completely freely, spontaneously, the hand guiding, not the mind. And so a kind of network is evolved upon the canvas, and from the intersecting lines, certain shapes and lines are chosen and consciously developed or refined, according to the artist’s aesthetic. Further, between each pair of lines is imagined and applied a colour, extending between the lines from point to point. Where the pairs of lines cross other pairs, so, too, do the colours. So new colours are born within the intersections in the same way as the shapes between the intersections are discovered. By this method colour and shape are thus two organic elements which cannot be regarded as separate, but only as an indivisible unity – they are born as one, together.

This represents the primary exercise, whereby the idea of organising and choosing shapes and forms is developed consciously. These shapes are still essentially flat – only two dimensional. Shapes so discovered may now take their place amongst other points and other discovered shapes, and again, by the same process, further organisation is possible. New shapes are discovered out of the old in an organic manner by a continuous process. But now the colours and disposition of the shapes develops a spatial quality which the first flat organisation of initial shapes lacked. Further, this spatial quality is in a constant state of movement, for it is related to no specific view point or horizon. Nor is it related to any particular number of view points or perspective frames. The forms exist simultaneously in all space and in all time they are viewed entirely outside space and time.

However, there is no reason why any previous convention should not be fused onto this method. But the important thing is that the method is in no way dependent upon them, and the most significant work is achieved when they are rejected.

Brian Claridge, Adelaide, Typed Manuscript attached to Letter, dated 30 June [c.1955].

Claridge was an architect who was Secretary and Vice-President of the Contemporary Art Society of South Australia, and before his death in 1979 was a Senior Lecturer in Architecture at the University of Adelaide.

[1] 1 “A mathematical formulation of the special theory of relativity was given by Minkowski. It is based on the idea that an event is specified by four coordinates, three

spatial coordinates and one time coordinate. These coordinates define a four-dimensional space and the motion of a particle can be described by a curve in this space, which is called Minkowski space-time … In special relativity the motion of a particle that is not acted upon by any forces is represented by a straight line in Minkowski space-time.” In Valerie H. Pitt (ed.), The Penguin Dictionary of Physics, (Penguin, 1977).

[2] Although there have been numerous translations over time, this quote is presumably taken from a contemporary edition of Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art.