A work-in-progress, 2024

I began this project officially mid-2023, even though I had started compiling information almost 40 years ago, in 1986, when I was working as a historian nearby to my parents’ house. I always had assumed it would be too difficult, and would be full of holes, but I guess I can only try and do my best. The process also offers an opportunity, with more experience under my belt, and perhaps a little more time than I had as a younger person (although not the energy and stamina), to question the assumptions and processes I adopted in developing previous survey exhibitions, catalogues, monographs, and the biography I had prepared (2001/2013/2018).

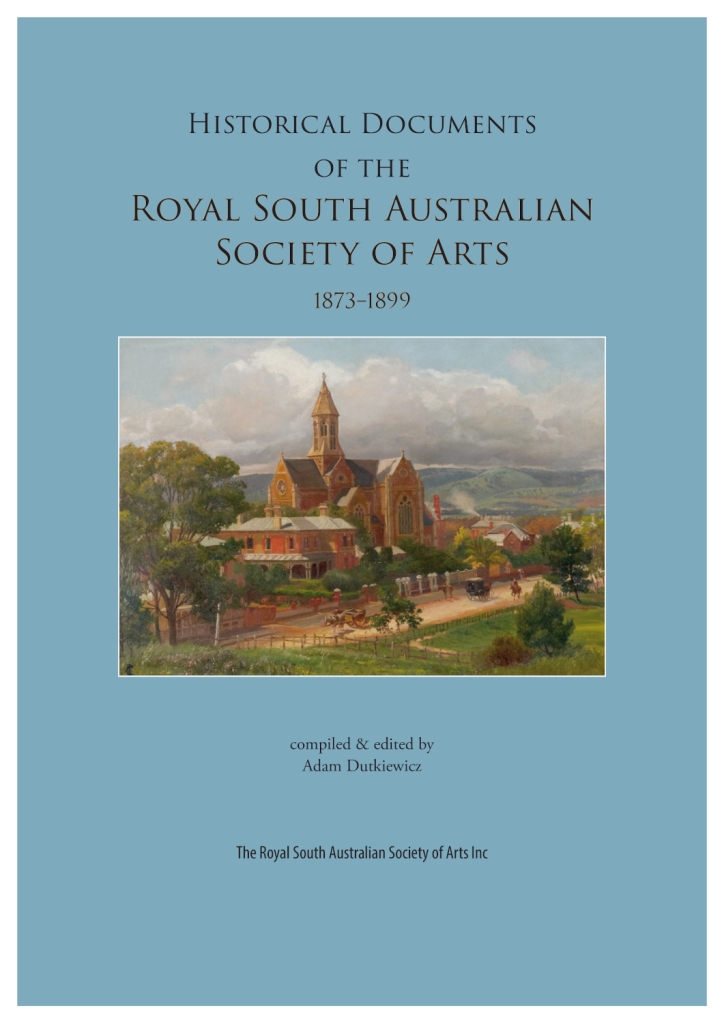

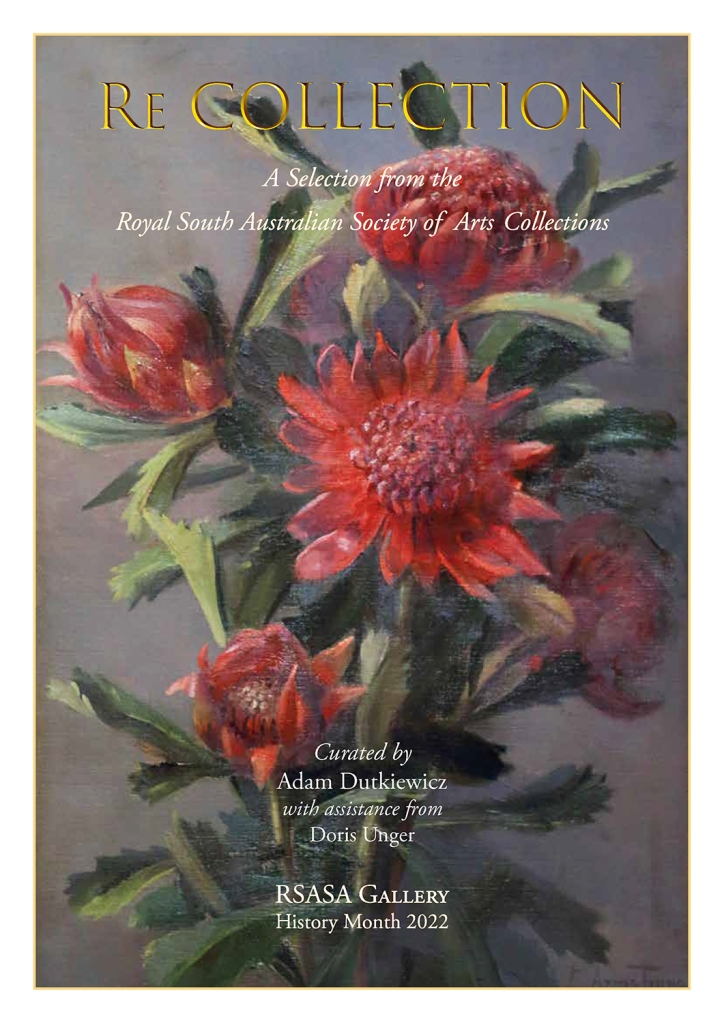

My method on this project is to work through all the catalogues I have (unfortunately several are missing), and art reviews that informed my earlier projects. Most of this material is now in the State Library of South Australia, with some in the Art Gallery of South Australia Research Library. There is also material in the Royal SA Society of Arts Archives that I call upon whenever working on this project.

It’s unfortunate that local art auction houses often disregard the original titles of works given by the artist, instead substituting a generic description of the work (eg “Abstract” or “Landscape”). Although this artist did use such titles occasionally, mostly he used poetic titles that related to his ideas or starting points in his abstract works, or some emotion he was trying to convey in a work. This bad curatorial practice obliterates the provenance of a work, and makes it almost impossible for scholars to trace its origin and thereby to date it.

Even though I wonder whether it is possible to achieve anything of great academic rigour in manufacturing this great “gruyere” cheese, I hope at least to correct errors, fill in gaps, and offer suggestions as to what something may actually be, but with a reason for my thinking. Let’s hope there will be more cheese than holes at the end of it. I am working by the decade, and thus far am into the third part, the 1960s, with three more decades to investigate thereafter. It’s already around 1000 entries, and I am not yet half-way finished (as a draft).

Of course, if you own one of his works, or know someone who does, please let me know. I am always interested to find works that I don’t recall, or may have missed as a child; or that were done before my time. It all helps!

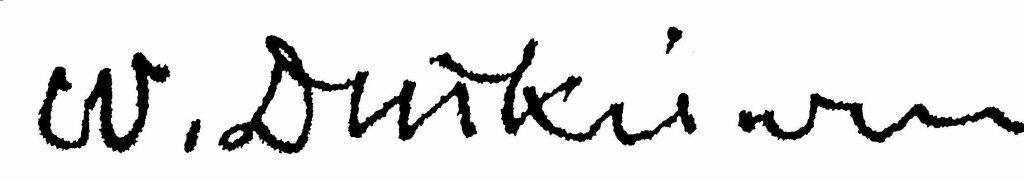

People can recognize his art by several signatures – “W. Dutkiewicz” was used on most of his black felt pen drawings, or initials. There are a range of signatures on his paintings — from the full signature “W. Dutkiewicz” to an abbreviated “Dutkie…” or initials. Very occasionally he reversed the initials, so “D.W.”, not “W.D”. Some were dated as part of the signature, some were not. I have elsewhere designated his shift from written-out signatures to initials from c.1954, when he starting using a weather-vane insignia on his large murals and wall panels, which soon condensed down to just initials.

As a general rule of thumb, unless obviously done later (such as with black felt pen, which he did roughly but not always from c.1970-89), they were painted in oils. I have even found some examples of the initials being made with a dry brush, without colour, into drying paint. They are ridiculously difficult to spot sometimes. From time to time, further information was stuck on the rear on a label, but often was written on in chalk, and sometimes black marker pen.

Signatures

I will post a few examples of his painting to show his varying signatures.

Painting signatures

Exam fever 1950

oil on balsa panel, dated & signed upper right Private Collection

Photograph: M Kluvanek